Serious about Sycamores!

A Great Blue Heron searches for lunch underneath the shadow of a massive Sycamore tree, a common sight throughout the Parklands.

The Sycamore tree is a staple of Eastern North American forests and can be found all throughout The Parklands. Whether you’re doing your morning jog on the Egg Lawn or paddling down Floyds Fork, these easily spotted sycamores stand proud and bright within the landscape. Their distinctive peeled bark creates a camouflage-like pattern, and as you travel up the tree, you’ll see sprawling branches sporting a smooth, elegant white bark. These stark white, ghost-like trees thrive in wetlands settings due to the extra moisture available, allowing them to grow up to 100 feet tall! Their preference for wetlands and highly moist environments makes the Parklands an ideal habitat for this species to thrive.

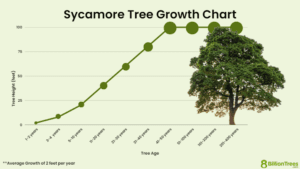

These fast growing trees are able to tolerate more extreme weather compared to other trees within our forest, especially in regards to moisture tolerance. In the ideal riparian environmental conditions, a sycamore can use the abundance of water and nutrient rich soil to achieve a growth rate of up to two feet per year! They are also a crucial component in the fight against stream bank erosion. Their extensive underground root system helps keep sediment locked in place.

Close-up view of a young Sycamore’s bark peeling near the Egg Lawn in Beckley Creek Park.

Bark peeling is commonly found throughout the plant kingdom. Sycamores aren’t the only trees in the Parklands that shed their bark; shagbark hickory trees are another abundant example. Both trees shed their bark during the summers – their peak growing season. As the trees grow each summer, the older bark is pushed outwards causing the outer layers to crack and peel. Underneath the raised strips of bark lining the sycamore, animals such as bats and small insects call these crevices home. While this peeling is often indicative of a health problem for other tree species, it’s a sign of good health for a sycamore.

While the mechanisms driving bark peeling is widely understood, the scientific community continues to speculate on exactly why these trees shed their bark. Some theories suppose that bark shedding may help the tree protect its leaves from leaf-eating herbivores. The herbivore’s camouflage is not nearly as effective when they’re traveling up the Sycamore’s white bark compared to the darker bark of other trees. Another possible theory for a Sycamore’s bark peeling could be as a self-defense mechanism. A tree that sheds its bark frequently may be less susceptible to fungi, parasites, and epiphytes spreading throughout its entire body. In reality, it is likely that the definitive answer to why these trees shed their bark are a combination of many of the current popular theories.

Whether you’re on the scenic Egg Lawn or taking a stroll down our Sycamore-covered trails (especially Valley of the Giants), take note of these white giants that stick out of the landscape. These sycamores are a vital component of our forests and will continue to provide valuable space for native birds and help stabilize our waterways.

A chart illustrating the rapid growth that a Sycamore undergoes in its first two decades in its life span.